|

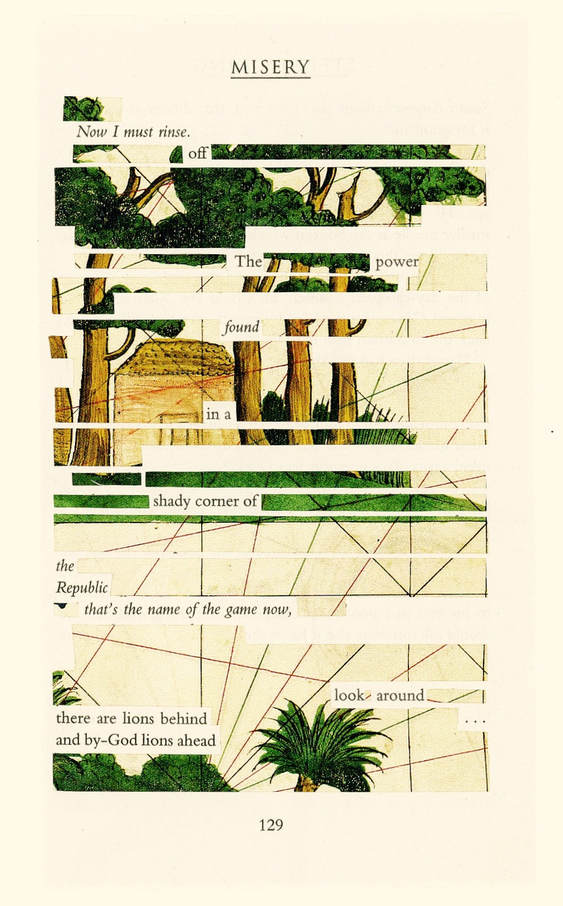

Selections from To Love The Coming End * Remember the days when I became a rhizome, a thing under your surveillance, something to cultivate? I was obsessed with being able to grow, to create an ideal environment for you and I. I tried to give you attention without possession. I felt the lust of science and soon, you became the subject. I studied you, no longer the root. I gave you soil. You said the conditions weren't right. That's reality, you said. Reality was a syn- onym for misfortune. I should have started the pills then. * There are many types of flora in Singapore. Parakeet flowers, orchids, bright flashes of red and hot yellow. Sculptural foliage, umbrella palms, and frangipanis. Different climate, dif- ferent kinds of life. I haven't gone to Jurong or to any of the reservoirs to explore nature. I don't know how to care for plants. How to care for living things. * Moist mountainsides, lush terrains for new shoots. Bamboo forests, a landscape of jade green and celadon. Variegated leaves rustle a game of telephone. * Singapore grows, a city of glass, as if there is no threat of plates and quakes. Previously published in To Love The Coming End by Chin Music. Leanne Dunic is a multidisciplinary artist, musician, and writer. Her work has won several honors, including the Alice Munro Short Story Contest, and has appeared in publications in Canada and abroad. Leanne is the Artistic Director of the Powell Street Festival Society, a Japanese Canadian arts and culture celebration, and is the singer/guitarist of The Deep Cove.Her debut book, To Love the Coming End, is a lyric-prose travelogue that moves between Singapore, Canada, and Japan, focusing on a disillusioned author obsessed with natural disasters, ‘the curse of 11’, and the loss of a loved one. Machine Testimonial 1 little robot, you grew up from when you were so young, just a pile of sensors & recycled parts from the trash. i tried to make you gorgeous. & you became such a gorgeous robot. beyond template & design. you're not so little anymore. when you walk on the street now, you glitter & gold. long time for you to realize that you light up like so. oh maker, you say at night, when humans are sleeping. i'm awake though, i hear you. i'm kinda like you too, i was made from all trash, you know? my parts more perishable than yours. believe me, robot. i want. i remember. my programming is nacent. i see you lying there open, waiting for me. & i think, i want to be good to you. my little automaton doll, take me up into the sky like it was promised in the book of machine love. Previously published in Love, Robot from The Operating System. Margaret Rhee is a poet, artist, and scholar. She is the author of chapbooks Yellow (Tinfish Press, 2011) and Radio Heart; or, How Robots Fall Out of Love (Finishing Line Press, 2015), nominated for a 2017 Elgin Award, Science Fiction Poetry Association. Her project The Kimchi Poetry Machine was selected for the Electronic Literature Collection Volume 3. Literary fellowships include Kundiman, Hedgebrook, and the Kathy Acker Fellowship. She received her Ph.D. from UC Berkeley in ethnic and new media studies. Currently, she is a Visiting Scholar at the NYU A/P/A Institute, and a Visiting Assistant Professor at SUNY Buffalo in the Department of Media Study. Chaos Theory for Beginners Listen there is yet a chance at madness to become the lioness in a field of moon lilies For words to push up from the known deep grow gills form feet wing through water’s skin We talk of doors but really we are only breaking walls Listen your eyes are so sky in that hurricane dress the hugest two moons I’ve ever Everything’s happening so slowly fast it’s hard to discern who needs repair and who is just mean enough to survive I mean isn’t chaos merely a loss space- defined the names of all the birds floating up like sheets freed from their lines and aren’t we all standing here on that flattest piece of earth shielding our eyes in our stormy clothes lilies at our brows stirring a little heat beneath our skirts just jonesing to rise Previously published in Tahoma Literary Review. Poet and photographer, Ronda Piszk Broatch is the author of Lake of Fallen Constellations, (MoonPath Press, 2015), Shedding Our Skins, and Some Other Eden, (2005). Seven-time Pushcart Prize nominee, Ronda is the recipient of an Artist Trust GAP Grant, a May Swenson Poetry Award finalist, and former editor of Crab Creek Review. Her journal publications include Atlanta Review, Prairie Schooner, Fourteen Hills, Mid-American Review, and Fire On Her Tongue: An Anthology of Contemporary Women's Poetry (Two Sylvias Press). from How to Write a Love Poem in a Time of War * Say you begin with midsummer. The haze of late June and dusk. The hush of birds lingering at the treetops above asphalt. How I am trying to be poetic, but then, isn’t all love a kind of elegy to something about to happen. The moment before or after the falling. Which is to say not precisely falling, but sinking slowly through water at an agreeable rate. Or stepping off a train platform and into a swarm of bees. Not precisely dangerous, but still fraught with danger. Not precisely desirous, but rattling with desire. * In the months after the election, no one can get comfortable in their skin. This wolfish thing inside me scratches at the door each night and howls. Growls at cab drivers and racist cousins in Oklahoma. Makes friends with any window I can climb out of. Anything that can get its hooks into my hair. When I was a kid, I kept getting tangled in the blackberry bush in the yard, scratches on my thighs, my arms, my hemline reddening with juice. Even my fingers sticky for full-on fever, that twinning under some July moon. I’d love to say I don’t hate men, but sometimes it’s hard. Each one before you, grooves in the same record—the ones with ex-wives and el caminos and whiskey in their voices. I’d love to say I loved them, but really, I was game for anything that could swallow me whole in one bite. * In April, in New Orleans at the Museum of Death, the only thing that disturbed me was the smell of it—death, that is. As if by association all those things carried a scent—letters from serial killers. faded clippings of autoerotic suffocations. Embalming tables and funeral dolls. The crime scene photo of Nicole Brown Simpson with her head come near clean off in a California courtyard. That sort of thing is as common as breathing, as common as the lingering smell of sickness and trash on Bourbon Street. Where a man I did not know shoved his face between my breasts and I was so startled I did not move. I and my sister barely blink at the film clip of the woman outside Chicago obliterated to a smear of red by a speeding train. The clip in judgement that proves fatal. The near miss that finally hits its mark. In the theatre, at the back of the storefront, we watch things die over and over on a loop, while Bourbon Street sweats neon and rots slowly. * Another summer and the bees have gotten unruly, swarming what they can—trash cans and train cars. Light posts in the middle of downtown. It’s the charm of the inexplicable, tiny wings glinting in the sun. How 20,000 of them in the UK followed a car where their queen was trapped for miles. That same summer, across the country, a rapist goes free. The girl still rolling over in the dirt behind a dumpster, pine needles in her hair and shoved rough inside her. It’s the same summer I am working out the problem of us like a knot. Another improbable, inexplicable thing. I’ve heard bees will work tirelessly to repair a damaged hive. Mend the seams between the wrecked and new until they are indecipherable. How they will, if prompted, repair other broken things—figurines, ice skates, Victorian doll houses. I want to think this is possible. To remake everything new eventually. The girl behind the dumpster covered in honey and rebuilding cell by cell. How each night, I am remaking something with the thrum of a hundred thousand wings. * Say you begin with a listing of every scar. Every broken bone. What the body knows as trauma or memory. Every love leaves a trace on the skeletal system, sometimes even a tiny stress fracture. As bodies, we move through the world occasionally bumping into things that damage us. When I was 8, I broke my left ring finger slamming it in the back door. My abdomen bears a scar from a teakettle incident. My forearm, the perfect triangle of the top of an iron. This is the way I move through the world. Occasionally bumping into the edges of bartending engineers and secretly married ad salesmen. Running into walls and tripping up stairs. I do not know how to write about love without a little bit of pain. The pure panic of its return. I only once said to a man that I loved him, and a decade later, it makes the bones of my throat ache. * I am really bad at telling jokes. Mixing up punchlines and losing my train of thought. Loosening my voewls and mucking up the perfect machine. I write poems called "How to Care for Your Princess Monster" and "How to Be an Emotional Ventroloquist" but I worry that while I'm pointing at my ribs, everyone is looking at my feet. Still I dream a lot about being trapped inside an enormous wedding cake—a claustrophobic swirl of sugar and lace. House fires and horses jumping from cliffs are easy, but where is the omen in so much sweetness? What else is there to do when the man comes looking for me with a bloodied shoe and a bottle of bourbon? Except hide inside the body of a huge, feather-bellied swan? I broke my ring finger once and it was all over for me. Understand that I am only looking for the sharpest item in the root to cut the girl from the swan that is the cake that is the swan. Previously published by dancing girl press. A writer and book artist working in both text and image, Kristy Bowen is the author of a number of chapbook, zine, and artist book projects, as well as six full-length collections of poetry/prose/hybrid work, including the recent SALVAGE (Black Lawrence Press, 2016) and MAJOR CHARACTERS IN MINOR FILMS (Sundress Publications, 2015). Her work has appeared extensively online and in print, including recent appearances in Paper Darts, Hobart, and interrupture. She lives in Chicago, where she runs dancing girl press & studio and spends much of her time writing, making papery things, and editing a chapbook series devoted to women authors. The Wind’s Measure

The length of the wind runs from mid-May to murder. The length of the wind runs from January through joy. The wind runs as long as the right hand’s first finger points to the sun after thunder. The wind gallops prayerward like a horse held in the palm of a rock, no taller than a knee bent for the sake of singing. The wind weighs more than the fossilized horse and stretches from fingernail to praise. The length of the wind runs from mid-May to mercy, January through justice. Unto the broken, dwelling in a broken, promised land, the wind drops a hammer and some are warmed and some are chilled and some laugh and some die. Silently through the nuclear physicist, the wind wicks loud as paper-scraps trailing in the wind’s wake, igniting an empiricist, fragrant through tallow. The wind strikes the wind like rice in a paddy. The wind scatters petals like blossoms of napalm. The wind snaps the backs of malnourished Conquistadores bowed down to gold. It is the wind who estimates poverty in moments by the method of moments, who assesses want in units of amass. It is the wind who shakes America by the ovaries, runs the length of revolution, all the calories in a dollar. The length of the wind runts from mid-March to hunger. The length of the wind grunts from Saturday through sorrow. The wind flutters nothing but orgasms and afterplay. The wind numbers seminarians more numinous than semen. The wind is a mote on the wind. The wind is the dust that measures time in footsteps. The wind is the word in the throat of the dust. The length of the wind runs from midwife to marvel. The wind ribbons out within mid-May and mourning and dust is the voice the wind whickers glory, the wind whickers grief. Previously published in Poetry. Peter Munro is a fisheries scientist who works in the Bering Sea, the Gulf of Alaska, the Aleutian Islands, and Seattle. Munro’s poems have been published in Poetry, the Beloit Poetry Journal, the Iowa Review, the Birmingham Poetry Review, Passages North, and elsewhere. Listen to more poems at www.munropoetry.com.  Sarah J. Sloat splits her time between Frankfurt and Barcelona, where she works in news. Her poems and prose have appeared in The Offing, The Journal and Sixth Finch, among other journals. She is currently working on a series of visual poems. She's on Instagram as @sjane30. Predators in an Abandoned Drive-In fig crinkle flickering/ culled oil celluloid/ rain hit bone hibernation no/ anemic cinema/ iceman on air ripe prairie throttled open snow/ northern spotted owl/ nettled photos worn netted protons howl/ air thin bone no/ on law born/ brawl on barn owl—predators? teardrops/ Dear ports/ (Auden’s chance edit)/ a hectic den/ a seined dune catch/ a catch died unseen sea slew/ seal sew/ aweless weasels/ shawl we tow dead elk wraith/ saw-whet owl/ death like draw (radiated whelk) red-tailed hawk Previously published in Crazyhorse. Jon Pineda is the author of the novel Let's No One Get Hurt (Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2018). His recent poetry collection Little Anodynes won the 2016 Library of Virginia Literary Award for Poetry. Some Boys When Brother's First Son asked me where it happened, where his father could not out run death, I tell him the truth, but feel heavy with the weight of witness, a wild gun shot ricochets in my throat. He wants to know if it happened in the back yard where his father as a boy once raced behind orange, and sweet lemon trees, scrambling over warped fences to escape bb gun games. Shoulders shot by other boys. Brother was a big target. Tiny bullets pierced summer skin but they smiled at the gun play with those they called brother. These easy pains heal clean. They are not the ones that mark some boys. Boys that always carry those scars, even after wounds are no longer circled red. Mother tells First Son not to wear his hoodie over his head. Don't walk to the corner store alone. Be back before the street lights turn on, she says, just like she told Brother as a boy. Are these the warnings Brother would have given his son, knowing that sometimes it is not enough because some boys, some brown boys are never just boys to some. Previously published in Raven Chronicles. Casandra Lopez is a Chicana and California Indian (Cahuilla/Tongva/ Luiseño) writer who’s received support from CantoMundo, Bread Loaf and Jackstraw. She’s been selected for residencies with the School of Advanced Research and Hedgebrook. Her chapbook, Where Bullet Breaks was published by the Sequoyah National Research Center and her poetry collection, Brother Bullet is forthcoming from University of Arizona. She’s a founding editor of As Us and teaches at Northwest Indian College. XXXII (from Utopia series) I am a girl in a white field. I am the son of astronauts. I am the mother and sister moving mountains, cutting moths. I am father and ghost from below the Bodhi tree. Previously published in Fourth and Sycamore. Bryan Edenfield was born in Arizona but has lived in Seattle since 2007. He was the founder and director of the small press and literary arts organization, Babel/Salvage. He hosted and curated the Glossophonic Showcase and the Ogopogo Performance Series. His writing has most recently been published in Construction Magazine, Meekling Review, Dryland, and Plinth. He is currently one of the Jack Straw Writers for 2018. Here is his website: http://wordlessdictionary.wordpress.com Sabbatical Keep doing the same things thinking something will change. Keep doing the work dumping out expectations that never rise full and hot. Keep rubbing oil where it hurts drinking vinegar waiting to be cleansed Stop allowing live things down there. Start living from somewhere else. Previously published by Fig Root Press. Seattle transplant, Jalayna Carter, is an emerging storyteller from St. Louis, MO. Her work is born of the tradition set by the Black Arts Movement through the lens of Poetry of Witness. It is just as much the result of a love of science-fiction and the re-imagining of personal history. She studied literature and journalism in the Midwest and from there developed an interest in interdisciplinary media. A 2018 Jack Straw Writer's Program fellow, she explores Immersive Poetry focusing on sensory stimulation through technology. She’s had pieces published by Third Point Press, Reality Beach, Puerto Del Sol and 2Leaf Press in the Anthology, Black Lives Have Always Mattered. You can find her on IG (@just.jalayna) and Twitter (@just_jalayna) talking about her plant babies. You can follow more of her work at www.JalaynaCarter.com. |

Blog HostNatasha Kochicheril Moni is a writer and a licensed naturopath in WA State. Enjoying this blog? Feel free to put a little coffee in Natasha's cup, right here. Archives

October 2019

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed